From Stockholm to Selmer: Tennessee’s down-home music culture draws international tourists

One doesn’t typically expect to find international tourists on the streets of a small, Southern town. But on any given day, you might just hear a conversation in German, or catch a snippet or two of a heavy Scottish brogue, on 2nd Street in Selmer, Tennessee.

The travel itinerary of one adventurous Belgian couple was bookended by stays in Memphis and Nashville where they naturally hit the hight points: Graceland; Beale Street; Stax and Sun Studios; Music Row; The Country Music Hall of Fame; and the heavily trafficked honky-tonks along Lower Broad. The couple planned two stops between Tennessee’s twin music meccas: Lynchburg and Selmer. As the home of Jack Daniels, one of the world’s most recognizable whiskey brands who just happens to offer samples on the distillery tour, Lynchburg was, perhaps, predictable. But Selmer, Tennessee?

Downtown Selmer has two red lights and all the small town charm you could ask for, but just like the more metropolitan destinations on the couple’s self-guided cultural tour, it was the depths of the town’s music traditions that got the Belgians off of I-40 roaming the rural backroads between Memphis and Nashville. They read about Selmer—the McNairy County seat—on a European travel blog, and the phrase that stuck in their minds was something like, “These hicks really know how to celebrate their heritage.” To put it another way, it was the cultural authenticity of the rural South that really appealed to them, and places like Selmer have it in spades. But as the travel blog would attest, what sets the town apart from the dozens of other Tennessee hamlets dotting the map is the way McNairy County residents have chosen to “celebrate their heritage.”

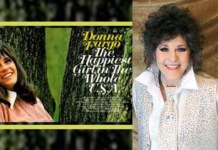

The most obvious feature, by far, in Selmer’s visual landscape is a pair of spectacular downtown murals which perfectly capture the ethos of the rockabilly era. Hicks or not, it’s a decidedly edgy look one might associate with a more urban setting. The first of the two monumental installations by Nashville artist Brian Tull went up in 2009, touching off something of a rockabilly renaissance in Southwest Tennessee. A music and cultural festival known as the Rockabilly Highway Revival soon followed, and then Rockabilly Park, Rockabilly Cafe, a music heritage themed walking trail, a guitar-shaped splash pad—the seemingly endless possibilities are still unfolding. By the time the second mural was added in 2012, the area’s music heritage had already become a point of pride among residents and a major draw for cultural tourists, especially roots music enthusiasts across the pond. The trend, and the world-class pop iconography, did not go unnoticed by state and regional tourism developers who have made liberal use of the images in overseas markets where American rockabilly music and musicians are still much venerated.

“When I first heard news of European travelers coming to Selmer for the murals,” said Tull, the real creative mind behind the renewed interest in this fading heritage, “I was a bit surprised; however, I knew of their subculture fascination with rockabilly and American roots music. Once I removed myself from being the center of the murals and painting them, and tried to look at them as a complete outsider, I saw their impact on the area in a grander scale. Pop, rock ‘n roll, country—they’re all offsprings of a common music. Roots music is the core, it’s where we’re from.”

He should know what he’s talking about. Brian Tull is a Selmer native and his region of origin was a hotbed of cultural cross-pollination that gave rise to rockabilly music and eventually rock ’n’ roll. It’s the stomping grounds of rock innovators such Elvis Presley and Carl Perkins who first met at a Presley concert five miles north of Selmer in a little town called Bethel Springs, Tennessee. And it was recently discovered that Perkins cut the first recordings of his illustrious career at a makeshift studio in Eastview, Tennessee, just a few miles south of town. “This is the epicenter of the rockabilly revolution,” added McNairy County Tourism Director, Jessica Huff, “and these murals are an incredible visual interpretation of our story. They say more in one glance than a handful of travel brochures. They are our billboard to the world.”

Rockabilly Highway Mural was Tull’s first successful painting on a grand, outdoor scale. Since then he’s been in demand as a muralist, completing projects in North Carolina, Mississippi, Chicago and Nashville. A second mural in Selmer, which most closely mirrors his photorealistic gallery works, is perhaps his public art pièce de résistance. Local and state arts agencies have also taken notice, offering generous funding—especially for the Tennessee murals. Each piece is an elaborately choreographed dance with paintbrushes, lifts, and ladders, set to a symphony of color that washes over the walls as the composition slowly emerges. It doesn’t take people long to realize something special is taking place in each new location.

As the weeks went by in Selmer, revealing a boot here, a guitar neck there, neighbors swung by daily to bring Tull a bottle of water, converse about the weather, or just check out the recent progress. Passersby pulled over in adjacent parking spots to watch Tull paint for hours at a time, as if it were a drive-in movie. The paint is dry and the murals are long done, but the traffic has never really slowed down. “My hope for both of these public murals,” Tull summed up his hometown work nicely, “is for people to see them, pause, and know that there is something special here—creativity, music, art, and rich roots music heritage. It may be hidden from the mainstream on a back porch, or a church on a back road somewhere, or it may have emanated from Sun Records; nonetheless, it’s amazing what you can see and hear in this rural region.”

For what it’s worth, an international audience agrees.

About The Author –

Shawn Pitts is an avocational folklore enthusiast, musician and writer living and working in West Tennessee. His writing has appeared in Southern Cultures, Tennessee Magazine, The Bitter Southerner, and The Tennessee Folklore Society Bulletin. In 2012 he was awarded by the American Folklife Center, Library of Congress for music heritage preservation efforts in his native Southwest Tennessee. Shawn is a past president of the Tennessee Folklore Society and currently serves on the boards of Humanities Tennessee and the Tennessee Arts Commission.